|

My Internship will be a Transition year through Anesthesiology. This will allow me to expand my knowledge base by working

with experienced residents and attendings in a number of different specialties. Below I have listed my schedule for the upcoming

year. As I transfer to a new service each month, I will try and post my experiences so everyone can stay up to date.

C-ya'

Andy

July Internal Medicine at the VA

August- Medical Intensive Care Unit

September- Hematology/Oncology

October- Neurology

November- Surgical Intensive Care Unit

December- Orthopedics

January- Neurosurgery

February- Adult ER

March- Anesthesia

April- Pediatric ER

May- Pediatric Clinic

June- Trauma Surgery

July 2004 - I will start the first year of my Emergency Medicine Residency

January

Well, this month I'm in the NeuroScience ICU (NSICU). This is another critical care unit in the Critical Care Tower at UMC.

One of the nurses told me there were only sixteen NSICUs in the country. Just another example of how UMC is on the cutting

edge of medicine and how the majority of Mississippi and the rest of the country are unaware.

Speaking of being in an exclusive group, I can't remember if I have talked about UMC's Critical Care Tower before. Many

hospitals have an ICU where the patients requiring constant monitoring are cared for. In most ICUs, you have a mixture of

critical patients. Within the same unit, there may be cardiac patients, stroke patients, surgical patients, and patients with

multiple medical problems. At UMC however, there is an entire critical care hospital with each floor dedicated to a certain

type of patient.

On the first floor is the Surgical ICU which cares for patients returning from surgery. Sometimes a patient may be too

sick or too severely injured to go immediately to surgery. These patients are also cared for in the SICU until they are stable

enough for surgery.

The second floor is dedicated to the Medical ICU which cares for patients with various kinds of medical problems. When

I was in the MICU, I helped take care of patients with multiple medical problems. We saw everything from overdoses, to renal

failure, to pulmonary failure, to liver failure. Sometimes, a patient may have two or more medical problems at the same time.

The third floor is dedicated to the Cardiac Care unit which cares for patients who have had severe heart attacks or heart

surgery. Once again, some of the patients are cared for in the CCU prior to surgery or, instead of surgery, because they are

too unstable to go to surgery.

The fourth floor is where I am this month. The NSICU cares for patients with brain or spinal cord injury and for patients

who have had a severe stroke. The tissue that makes up the brain and spinal cord is exquisitely delicate. Last month I was

on Ortho trauma and the Ortho docs would go in with drills, saws, plates, and screws and reconstruct and/or reinforce shattered

bones. Then, the bones would heal and grow back together.

When the brain or spinal cord is injured, you can't go in with plates and screws. And, the tissue of the brain and spinal

column is not capable of repairing itself. The neurosurgeons do however, have other strategies. The brain is located in the

hard bony skull for protection and yet, this is also the main problem when the brain is injured. The brain wants to swell

like any other tissue that has been injured but it can't. So, as it is being compressed, more tissue is being damaged which

causes more swelling. So, one of the things I've learned so far is the various ways to keep the brain from swelling. The neurosurgeons

may insert a drain or, they may actually cut away some of the skull to allow the brain to swell. Then there are the various

medicines, methods of ventilation, IV fluids, and patient position to also help keep the swelling down.

Well, after only two nights on call, I have already learned a lot. Since these patients are in the neuroscienceICU, it

goes without saying that they have critical neurological injuries. The first night I was on call I had to learn how to go

through the steps to pronounce someone "brain dead" which was unfortunate.

As with all of the other ICUs I have worked in this year, the Attendings (doctors) and nurses are wonderful and extremely

talented. As I mentioned before, instead of having staff taking care of different kinds of patients, each floor of the critical

care tower is dedicated to a specific kind of patients. This allows the nursing staff to become extremely proficient in their

duties. Granted, I may have the MD behind my name but, I'd be foolish to not listen to the years and years of experience surrounding

me. I'm just grateful that they are so understanding while working with a new doc.

Anyway, one of my New Year Resolutions is to try and keep my website up to date since I'm getting back home even more

infrequently than before. I'll try and keep everyone posted.

December

This month has been a major shift in gears. In the ICU units we only had 3

to 5 patients and we were keeping up with every detail of their care. This month I was on the Ortho Trauma service. I was

told that the "Rotators" (the interns who work on the service who are not orthopedic residents) see after the patients on

3 South. Well, guess what. There are usually somewhere between 12 to 16 patients on the Ortho Trauma service on 3 South. There

is no way you can spend 30 - 45 minutes on each patient in the morning before the 6:30 conference the orthopedic service has

each morning. So, I found out that the ortho service really has to have a focused approach to examining the patients and to

doing the notes. Now, the only ortho rotation I had done before this was one week during my M3 year. So, I really felt like

a fish-out-of-water. So, with the increase in the number of patients and being somewhat unfamiliar with the requirements

of the ortho exam, I was trying to get to the hospital between 4:00 and 4:30 am. The first day, I was asked

if I had seen what kind of range of motion a patient had and I was like, "No, they just had surgery two days ago." But, that's

why they put the plates and screws in during surgery. This allows the patient to get back on their feet quicker. Unlike 30

years ago when I broke my femur (thigh bone). I was in traction lying in a hospital bed from September to December.

Speaking of traction, that has changed a lot also. They used a manual drill

to put my traction pin in. Today, they use a big, heavy-duty rechargeable drill. I got to help put several traction pins in

and I must say, this is another example when it's better to give than to receive.

One of the things I try and get out of these different rotations is to learn

what needs to be done before calling in a consultation. One of the things I learned on this rotation is that all fractures

don't automatically become primary ortho patients. For example, one lady came in with a fractured hip. She obviously had an

orthopedic problem but, she also had a history of cardiac problems, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Since she was having

an irregular heart beat, she was admitted to the cardiac service who became the primary service.

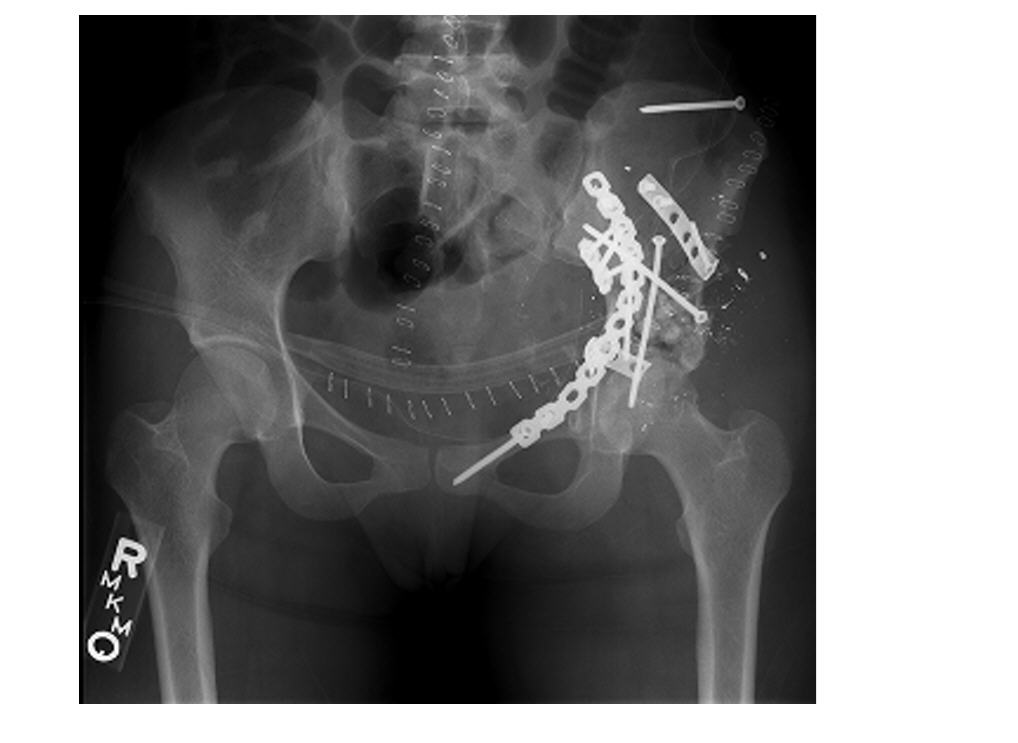

Once again, UMC gets all of the difficult cases. We had two patients transferred

in from other orthopedic surgeons after the patients had already had multiple surgical failures. At the beginning of the rotation,

I saw the x-rays and CT scans of some of the patients and thought, "No Way." But, because of the expertise of the Attendings

and the ample opportunities to operate, the really complex surgeries become commonplace.

Since I am a non-surgeon, I would try and take care of all of the problems

that occurred on the floor and allow the surgeons to do surgery. Another one of my tasks was to collect all of the CT scans

and x-rays done on the patients. This also helped me in knowing what kinds of x-rays to order in the future. I also got plenty

of opportunities to put splints and casts on patients.

Once again, I was surrounded by awesome residents and nurses. It seems that

the busier a service is, the more important that there is a "team" mentality. It was no different this month and the best

personal example I had was on Christmas morning. I had only seen 2 or 3 of my patients when one of the nurses asked me to

come to a patient's room. The patient was actually on another ortho service but, she had a drop in her mental status and was

not oxygenating and I was the only MD on the floor at the time. Always go back to your basics and go through your ABCs. By

the time we had her stabilized, ordered a STAT CT scan, and transfer papers done to transfer her to a monitored bed, I had

spent about 45 minutes with her. I knew there was no way I was going to be able to see all of my patients before the morning

conference. But, before I knew it, there were 3 other senior residents from other ortho services on 3 West helping me see

my patients. All of the patients were seen before conference and I was really appreciative of the help they gave me since

it allowed me to get out of the hospital sooner and spend as much of Christmas as possible with DGA, CC, and KT.

Well, I'm at the half-way point in my intern year. Six months down and only

six months to go before I start my Emergency Medicine residency. I will spend January in the NeuroScience ICU (NSICU). I'll

try and make some more up dates a bit more regular for the rest of the year.

Take Care, God Bless, and HAPPY NEW YEAR EVERYONE!

| An example of the handy work the Ortho docs do. |

|

| Pelvic repair after being shot with high power rifle. |

| Before |

|

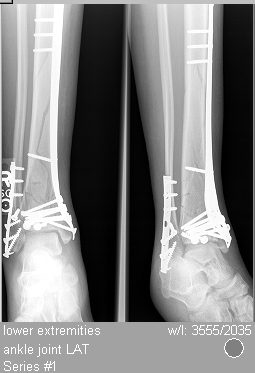

| Fractured lower leg |

| After Repair |

|

| Repair of lower leg fracture |

November

Well, I got my wish for wanting more "excitement." This month I'm in the SICU,

which is the ICU for surgery patients. The same still holds true. Some really sick and injured patients come to UMC. About

half of the patients in the SICU were transported to UMC by Air Care helicopter. I told DGA today that it's pretty bad that

out of my five patients the one that is doing the best is the one the TREE FELL ON breaking all of his ribs on one side and

collapsing his lung.

I'm glad that I had already done my MICU rotation. Since there are not as

many residents working in the SICU, each resident has to take on more responsibility. Because of my MICU rotation, I felt

like I was prepared for the tasks at hand. Once again, we had to track everything. The most time consuming part of this rotation

is having to write down all of the information each morning. We usually averaged 3 to 5 patients each. Since I have a habit

of wanting things to look "just right" (yes, I have been accused of being anal retentive before) I was getting to the unit

between 5:30 and 6:00 each morning. The plus side of getting in early is that you also get to leave early if you are not on

call.

Anyway, I got plenty of opportunities to continue to develop my skills. I

got to put in 4 or 5 chest tubes, several arterial lines, and a chance to do some intubations

Once again, my first on call night was my worse. I had a patient that one

of the other residents had been following who wasn't doing well. I spent all night adjusting IV medicines, fluid rates, changing

ventilator settings, and following labs. I had also called the attending to give him updates and gather advice on what to

do next throughout the night. Because of everything that had been done, I had to spend extra time doing her daily note so

I would be prepared for morning rounds. However, when the family visited at 6:00 a.m., they finally accepted the futility

of our efforts and accepted that we were only prolonging the inevitable. They made the most difficult and yet, the most humane

decision a family has to make. They decided to withdraw all of the medicines we were using to artificially keep her blood

pressure up. They decided to make her comfortable and let nature take its course.

Some of the patients admitted to the unit where there just for post-surgery

observation. Some of them however, went out of the way to do something to get themselves admitted. For example, we had one

guy, who I assume fell asleep, drove his 18-wheeler into a bridge and had multiple fractures and internal injuries. Speaking

of internal injuries, we had two patients who were admitted at different times with a tear in their aorta (the big vessel

that comes off of the heart) and their abdominal organs pushed up through their diaphragm and into their chest cavity. Once

again, the skill and expertise of the doctors and staff at UMC proves to be life-saving. Both survived their initial injuries

and were moved from the SICU to a room on the floor. Granted, neither one will ever be back to their pre-accident condition

but, they didn't die from their injuries either.

Another aspect I enjoyed was working with the nurse practitioners (NP) in

the SICU. I was able to learn a lot and appreciated all of the help they gave me during the rotation. The NPs are the stability

factor. They are there in the unit and on the Trauma service every month. So, as new residents rotate in on the first of every

month, the NPs can bring them up to speed on the problems and goals of all the patients already admitted to the unit. Also,

they are trained to do a number of advanced invasive techniques like chest tubes, central lines, etc. They also help the residents

out in other ways. For example, since I'm not a surgery resident, I do not get to work as closely with the surgery Attendings

as some of the other residents. So, it was nice to be advised ahead of time that this particular Attending likes to use these

antibiotics or this other Attending likes you to have already done this or checked that.

Once again, the nursing staff was tremendous. It was also such a contrast

when compared to the autonomy of the nurses at the VA. While I was at the VA, the nurses couldn't do anything without

an order. They may ask you to give the order but they wouldn't do anything without an order. In the different ICU units at

UMC, you have a dedicated staff working day in and day out with the different Attendings and Residents. So, after working

in this type of environment they know that if the patient does __________ then they are going to get an order to do __________.

Because of this, they can easily predict what needs to be done and will go ahead and write a "verbal order" so they can do

what needs to be done. Since you are constantly rounding on each patient in the unit, the next time they see you they tell

you what was done and you just sign the orders. Initially, I was wondering about this. But, with 18 patients in the unit and

you being the only resident in the unit at night, you would physically wear yourself out if you had to constantly run from

one end of the unit to the other just to order a blood gas or to make a medication change or vent change. By the end of the

month, I had learned to really appreciate the nursing staff and all that they do to care for the patients.

October

This was my month for Neurology, which got off to a really bad start. First

of all, I had no communication with the department ahead of time giving me any kind of instructions on where to go or what

to do on my first day of the rotation. Since we were so busy on the Cardiology service in September, I never called to find

out what was going on. That was a big mistake. When I arrived on the Neurology floor on the first day of my rotation, I noticed

several problems. 1) They did not have the current month posted with a schedule of who's on call. 2) When I found the correct

on-call list, I'm not on the list. Initially I thought, "Cool! No call for the month." Then I noticed I wasn't assigned to

anything. I go downstairs to talk to one of the other emergency medicine interns who had just gotten off the Neurology rotation.

He tells me that everyone will be meeting at Methodist Rehab for morning rounds.

So, I make it to the meeting on time and I meet the Chief Resident who tells

me that Im not on the schedule because I'm not suppose to be rotating with Neurology in October. I had already thought of

this possibility and I had checked the master schedule I was given. On the master schedule, I was listed to do a Neurology

rotation in October. When I mentioned this, I was told that I might have to do the rotation "next month." No, next month and

every month after that, I'm already scheduled to do a rotation somewhere else. Then I was told that they would have to get

with my program coordinator to see when I could make up the rotation since the schedule was already made up and everyone was

already assigned and the call schedule for the month was basically finished. Needless to say, I was starting to feel a bit

frustrated.

After Grand Rounds, I followed the Chief Resident back to the VA where

she picked up her copy of the master schedule that was sent to her and she pointed and said, "See, we already have an intern

from anesthesia rotating with us this month." I looked and said, "Oh, there's my name, right there." Not only was my name

on the list, it was highlighted. I will say, from

that point on, the Chief resident did go out of her way to accommodate me. I started at the VA taking care of neuro patients

admitted to the hospital. Then, I went to the VA Neurology consult service. Then I went to the UMC Ward team that takes care

of the neuro patients admitted to the hospital. I was hoping to be transferred to the UMC Consult service since I felt I would

benefit from seeing and doing the initial neuro exam on patients as they initially presented to the service. Instead, I spent

the rest of my rotation working with the team taking care of Neurology patients admitted to UMC.

Let me say this before I go any further. The Neurology service does a lot

of really good things for patients with chronic disease. There are many patients whose quality of life has improved tremendously

because of the advances in neuroscience. We had a patient come in who could barely walk and depended on a wheelchair to get

around. By the end of the week, she was walking out into the hall with the help of a walker.

However, just as everyone doesn't like chocolate ice cream, it's only natural

that there are some aspects of medicine that doesnt appeal to everyone. Neurology just didnt get me real excited. It's probably

because of the lack of technical procedures. About the only procedure they do a lot of is a lumbar puncture. This lack of

technical procedures became obvious one day when the nurses told me that they could not get an IV on a patient after two days

of trying. I reverted back to my secret weapon and started another EJ (see cardiac arrest in September.) When I reported to

the senior resident what I had done I was told I wasn't allowed to "start any lines." I was supposed to contact Surgery. I

pointed out that I was not starting a central line but an IV. When she continued telling me I "couldn't do that" I got a bit

frustrated and told her I was not going to consult surgery to start an IV for me.

Anyway, as usual I learned a lot while working on a focused rotation. Like

I said before, it just wasn't my cup of tea.

September

Ah ha....Cardiology, one of my real interests points in medicine. I guess

one of the reasons why I like trauma and cardiology so much is because of the way Paramedics are trained. When the first Paramedic

course was put together, it was felt that Paramedics could save the most lives if they could stabilize trauma patients and

treat cardiac arrest. Because of this philosophy, a large part of the Paramedic training curriculum deals with trauma and

cardiology.

First of all, let me say its true. Mississippi is the center for out of control

high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, smoking, and generally poor life style habits (Okay, how many of you reading

this gets at least 30 minutes of aerobic exercise three times a week and follow a low-cholesterol, low-fat diet?) Needless

to say, the cardiology service has been one of the busiest services I have worked on. Once again, I lucked out and was teamed

up with some really great residents. (Josh may not feel the same way since this is the second rotation he's had me tugging

on his coat trying to keep up) Billy, the Cardiology Fellow who headed up the team, was awesome and made a really busy

service a pleasure to be on. Even though we were really busy, Billy always looked for opportunities to teach me the things

I need to know when I start taking care of cardiac patients in the ER.

BTW, a "Fellow" can be a guy or girl. The term Fellow applies to someone who

has already completed a residency program and is doing additional training in a certain specialty. For example, before someone

becomes a heart doctor, lung doctor, kidney doctor, etc. they must first do an Internal Medicine residency that covers adult

medicine problems.

Anyway, once again I was shown how the really sick patients get transferred

to UMC. One of the cardiac markers we check to see if someone is having a heart attack is called Troponin which is usually

less than 0.04 in someone who is NOT having a heart attack. Between 0.04 and 1.0 is a gray zone and you have to take other

things into consideration. If the patients level is >1.0, it is likely that they are having a heart attack. Well, one of

the patients transferred to us from another hospital had a Troponin of 783!! I felt pretty comfortable in telling the wife

that he really did have a heart attack instead of waiting for the patient to come back from the heart cath lab.

I also got a chance to work with Dr. Bennett who someone referred to as a

"Diagnostic Ninja" because he can arrive at a diagnosis before you can even think about ordering any kind of a test. I was

reading the ECHO report (like an ultrasound of the heart) on one of my patients and mentioned that the ECHO had picked up

and anterior wall aneurysm and he goes, "of course it did. It's pretty big. Didn't you feel it?" Then he takes my hand and

places it on the patients chest and explains to me that what I'm feeling is part of the heart bulging out during contraction.

On another patient, he takes a pen a places it on the patients chest and says, "See that split S2?" Well, no. A split S2 means

two of the heart valves that are suppose to close at the same time are actually closing at different times. I have a really

hard time hearing a split S2 much less seeing a split S2.

Once again, I got to work with a dedicated staff of nurses who focused on

cardiac patients. They really helped me out a lot, especially my first night on call. Because of the way the month fell, I

had to spend 11 nights at UMC while on my MICU rotation. So, I thought spending only 7 nights on call during my cardiology

rotation would be a breeze......WRONG!!! Did I happen to mention how many cardiac patients are admitted to UMC? Also, the

really bad sick cardiac patients are located in the new Critical Care Tower. The not as sick cardiac patients are on 2 West

in the regular hospital. So, you are constantly running back and forth between the two buildings while on call.

On the morning of my first call night, I put my bags in my call room bed and

pretty much didn't go back into my call room until the next AFTERNOON when I got my things to leave. It seems like everything

went wrong, I had a heart transplant patient with a new onset of seizures, a patient being transferred in from an out of town

hospital, and a patient decompensating who eventually went into cardiac arrest.

While I hate that a patient I was taking care of went into cardiac arrest

(i.e., his heart stopped) I'm glad I had my Paramedic training. The way the hospital has it set up; there is a dedicated group

to respond to a patient going into cardiac arrest anywhere in the hospital. They all have "code pagers" which go off and announce

where they need to respond. Well, since my patient was already starting to have problems, I was already on the floor going

through his chart at the nurses station. Suddenly, I heard a woman screaming, "He's dead! He's dead! She killed my baby!"

Usually, this isn't a good sign. Especially when you hear it in a hospital around 1:00 in the morning. As I'm going toward

the screaming woman, (who runs past me) the nurse comes out and says, "I just gave him a sip of water to help him take his

medicine. I think he may have choked." So, we go in and roll the patient onto his side to clear his airway and while I'm holding

him on his side I feel a very weak pulse. When we lose the pulse we roll him onto his back and called for the "Code Team."

Now then, did I wait for the Code Team to arrive before we started doing something besides basic CPR? Of course not! The Code

Cart (that is at every nurses station) was brought into the room. The Code Cart has everything needed to run a Code. BTW,

running a "code" means doing everything possible to treat someone who has gone into cardiac arrest. Anyway, I was putting

an ET tube down (a breathing tube to help get oxygen into the lungs and not the stomach) when the Code Team arrived. Then,

the Chief Resident on the Code Team asked for a triple lumen set which is a really big IV that goes into a really big

vein (remember what happened to me in the MICU?) For some reason, the medicine residents just love starting triple lumens

during a code. I have wondered about this since it takes longer to do than a peripheral IV and since you can deliver more

fluid faster with a large bore IV. Since I knew this situation might come up during my rotation, I had started carrying a

14 gauge IV cath in my lab coat pocket, just in case. So, while the resident was opening up his triple lumen kit, I was turning

the patients head to the side to expose his external jugular vein (the big vein you see on the side of your neck.) I had the

IV actually started before the nurses had the bag of IV fluid spiked with the tubing. The resident asked me if it was a good

line and I briefly removed my finger from holding pressure to see the blood flow (and those of you who have done this know

what kind of flow you get with a 14 gauge in an EJ.) Needless to say, he abandoned his attempt to start his triple lumen.

We worked the code aggressively and actually got a pulse back. We called transport

to move him to the MICU. Unfortunately, before we could get him out of the room, he went into cardiac arrest again and we

couldn't get a pulse back a second time.

While we did have a few patients die during this rotation, there were a large number of patients

that did very well.

Without a doubt, this rotation has been AWESOME. Great Attendings, great Residents,

and a great staff surrounded me. I learned a lot, which will hopefully payoff when I get into the ER. If there is anyway possible,

I'm going to try and do another Cardiology rotation.

August

In August I was assigned to work in the Medical ICU at UMC. Now, most every town

has an ICU where they care for really sick patients. But, sometimes they have patients they may feel are "too sick" to be

cared for in their ICU and guess where they send them. Yep, to UMC. So, we not only have "typical" ICU patient (pneumonia,

overdose, heart failure, etc.) we also have patients with multiple problems. We had one patient who had congestive heart failure

(which was worsened after having a heart attack), respiratory failure (requiring mechanical ventilation), sepsis (from a severe

urinary tract infection), liver failure, and a GI bleed. About the only organ that did not have a problem was his brain (CT

did not show any abnormalities.) Unfortunately, he had too many problems for him to recover and, his advanced age was working

against him. We were however, able to help keep him alive until all of his children and grandchildren from out of state made

it to Jackson. Even though he was not conscious at the time of his death, I'm sure it would have meant a lot to him to know

that his family and close friends surrounded him.

Dealing with MICU patients also brings the responsibility of telling family members

how their loved ones are doing. When the patients are getting better, it's no problem. When you know that there is a high

probability the patient is going to die, it's a lot harder. You don't want to give them false hope but you don't want to be

too brutally honest either. I will say this; UMC has some really good doctors in the MICU. There have been several patients

that on initial presentation, I didn't think would survive the night, much less being discharged from the unit. And yet, many

of them did get better.

One thing that working in the MICU has done for me is that it has forced me to keep

track of a lot of details. When you are dealing with really sick patients, it seems as if everything impacts how quickly they

are going to get better. We track their fluids, calories, nutrition, and of course, all of the medicines, tests, and consults.

We also see every patient multiple times throughout the day. We sometimes have labs that we have to check every one to three

hours which isn't that bad at three in the afternoon. However, at three in the morning, it gets old quick.

We have three teams looking after the MICU patients which means every third night,

my partner (a more experienced, senior resident) and I have to spend the night in the MICU. So far, we have only had a few

really bad nights. One night I had a patient who had overdosed come in from an outside hospital with all kinds of abnormal

lab values. (Some were not compatible with life, like a pH of <7.000) That was one of the nights I was checking labs almost

every hour from 1 a.m. until the time we rounded the next morning.

I have also had the opportunity to do a lot of different procedures this month. We

had one patient who was going downhill fast and we needed a central line (a big IV in one of the big veins like the femoral

or internal jugular.) This was one of the times when my experiences as a paramedic paid off. As a medic you get used to working

fast on patients who are about to die. One resident was on one side of the patient starting an arterial line so we could continuously

monitor the patient's blood pressure. Nurses were squeezing the IV bags to try and increase the patients blood pressure. However,

they were trying to do this through a small IV catheter, which is why I was on the other side starting a central line in the

femoral vein. After we had the arterial line and central line started we were able to stabilize his blood pressure. Looking

back, it was one of those times when everyone had something to do and because of focused teamwork, all of the tasks were accomplished

quickly and efficiently.

Speaking of starting IVs, in Paramedic school we were warned of the complications

like bleeding, infection, and the ultimate fear....... the shearing of the catheter tip causing an embolus. Starting a triple

lumen central line I found out has its own unique set of complications. We had a patient come in who was unresponsive and

had a previous history of threatening suicide. Her blood pressure was going down and I was asked to put a central line in

the internal jugular vein in the neck. Well, I had problems and one of the senior residents took over. Her pressures continued

to drop and her oxygen saturation dropped. We stopped what we were doing and started manually ventilating her. Another resident

started a triple lumen in her femoral vein since he could get access there easily. We got a chest x-ray because she was becoming

difficult to bag and we suspected a possible pneumothorax. Well, x-ray showed fluid, not air. The Critical Care Fellow put

in a chest tube and got back over 1L of blood. Cardiovascular surgery was called to take the patient immediately to surgery.

Unfortunately, she went into cardiac arrest several times and did not survive. In surgery, it was discovered that one of her

arteries had been nicked. This really bothered me. Luckily, I had an attending that intuitively knew how I was feeling and

pointed out the following. 1) I was being monitored by a senior resident, a Critical Care Fellow, and the Critical Care Attending

and no obvious poor techniques were identified while I done my procedure. 2) I was not the only one who attempted to start

the line. 3) Puncturing an artery is a known complication of doing a central line. And then the big one 4) The results from

the rest of her labs had came in and her INR was almost 11!!!! The INR is a test to see how well the blood is being "thinned

out" when a patient is on Coumadin. Someone who is not on a "blood thinner" will have an INR around 1.0. The usual goal for

someone on Coumadin is to have an INR between 2.0 - 3.0. Her INR was >10. So, the same stick in someone else would most

likely not have had the same outcome. We never did find out what she took to get her INR so high. However, in looking back

through previous records we saw where she had threatened to take "rat poison" which is a concentrated form of Coumadin. By

the way, I hate to be the bearer of bad news but, if you are on Coumadin then you are taking the same stuff in rat poison.

SURPRISE!!!

Anyway, its hard to believe that my first two months as an intern are almost over.

Next month I start working with Cardiology. I will also be going to Birmingham next month to take an Experienced Providers

(EP) ACLS course. Apparently, there is not an EP course being taught in Mississippi and I was asked if I would like to become

one of the new EP instructors. Of course, you have to take the course before you can teach the course. So, I'm looking forward

to that.

I feel very fortunate to have been given the opportunity to work in the MICU with

Dr. Wilson who was my Attending for the majority of the month. Not only did he help teach me how to manage difficult patients;

he also helped teach me how to manage all of the paperwork and small details that can be easily overlooked. I hope to have

another opportunity to work with him again in the future.

JULY

My first month of working as a new physician was at the VA Hospital on the Medicine service. The patients

in the hospital are assigned to different "teams" or groups. For example, people with fractures are taken care of by the "Orthopedic

team", people with surgical problems are taken care of by the "Surgical team", and people with heart problems, lung problems,

are some other medical problem is taken care by one of the "Medicine teams." Of course, some patients are so sick they are

in the ICU. For other patients, a sub-specialty team, like Cardiology, Neurology, etc. may care for patients with

a specific.

The transition from student to physician is a bit intimidating. After all, only two months earlier I was being

referred to as a "student" and now they are asking the "doctor" what to do. The thing that was most intimidating was when

I was on call. Each team takes turns spending the night in the hospital and being responsible for all of the medicine patients

in the hospital. It's one thing when a nurse calls and asks questions about a patient on your team that you are familiar with.

It's completely different when they call and ask a question about a patient on another team that you know nothing about. Luckily,

the VA has a really awesome computer system. For example, when I was asked about increasing the high blood pressure medicine

for a patient, I could look up the patients history and find out if the primary team wanted the patients blood pressure to

stay within a certain range. Or, they may have had a reason to take away the patients high blood pressure medicine.

I also had a chance to start taking care of patients and really feel the pressure that they were depending on

me. As a student, I could write orders but they weren't acted on until a resident signed behind me. Now, the orders are not

done unless I write the orders. On one hand, you are so afraid that you are going to miss something, you want to order every

lab that is done in the hospital. But, you have to remember that someone has to pay for those labs and you only need to order

those labs that will possibly guide and/or change the way you care for your patient.

All in all, July was a really great month. I got to work with some very good nurses who were considerate of

me just starting to work as a doctor. They would point out things that I had overlooked (Do you want to order a ______ test

also?) They were also helpful in trying to figure out how to get things done within the VA system. Even though it is a hospital

it is also a part of the federal government so, red tape and rules that don't make sense exist also. They also helped me when

I had to figure out how to do all of the paperwork for when a patient dies. (Not one of my patients, mind you. It was a patient

on another team.)

All in all, July was a great month for the start of my medical career.

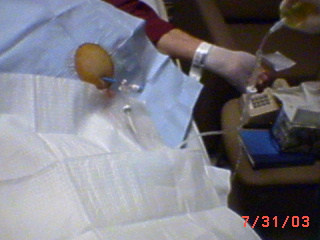

| Patient with liver damage. |

|

| Notice the excessive amount of ascitic fluid |

|

| We needed a LONG needle for this. |

| Draining off the fluid. |

|

| We drained six liters of fluid from his abdomen. |

|

| Four of the six liters we drained off. |

|